When we first start a practice of meditation, we can often feel an enthusiasm or excitement. This can be likened to that of a new hobby that we throw ourselves into headlong or the freshness of a new relationship with all its desires and expectations. My teacher Baba Hari Dass (Babaji) once said, “at first the ego likes the idea of being a yogi,” but over time an upwelling of subconscious material can start to rise to the surface of the mind. This seems to be a shared experience with many aspirants on the path of daily meditation. What arises may be vastly different for each person, but there are some common threads worth exploring. Over several decades of talking with students in my classes or in consultation at my Āyurvedic clinic, some of the things that seem to crop up for people are a sense of boredom, restlessness, or a feeling of not being “good” at meditating. Other people say that their minds are just too busy to focus on the practice, so they give up quickly.

An important thing to remember here is that it takes practice, a lot of practice, to stabilize the mind, and these experiences are shared by anyone who has tried to meditate, especially in the initial phases. Even after years of meditating, there is much variability in the quality of concentration and ability to access deeper meditative absorption.

In rare cases, a person might appear to be a natural at meditation. But as many respected teachers have pointed out, this may be due to past saṃskāras (tendencies) that may arise early in life and which are traditionally believed to have been cultivated in previous incarnations. Regardless of our personal faith or beliefs, concentration is a muscle that must be strengthened through persistent practice in order to yield fruit. Once a practice bears fruit, we taste its juice and start to crave it. The well-worn groove of discipline allows sādhana (practice) to become a habit.

When we sit day after day, and the initial honeymoon phase of regular sādhana has settled down, we come face to face with ourselves and the melange of thoughts, feelings, and emotions that have found refuge in the periphery of the mind. These aspects of the psyche start to percolate up into our awareness. I liken this to the proverbial hellhounds on our trail; ones that eventually catch up to us to nip at our heels as we slow down, sit down, and engage in sādhana.

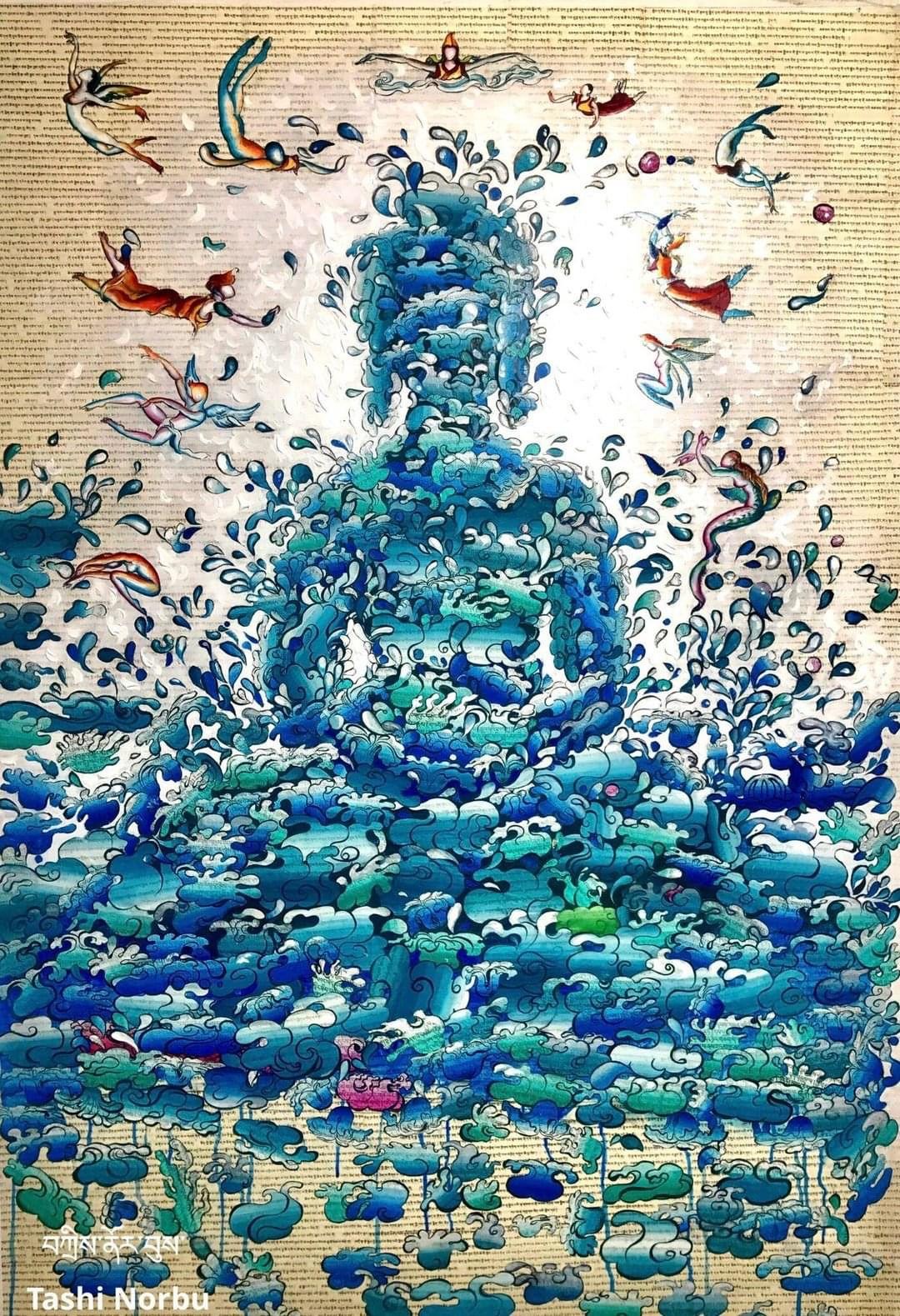

When we are busy going about all of the duties and obligations of life, there is much that is kept at bay. As we step into the threshold of the present, much starts to appear in the forefront of our experience. As we attempt to keep the mind one pointed on any technique or method, we can become weary of the distracted mind and the many elements that can arise. We might begin to think that we are just not good at meditation, or that it is a futile waste of our precious time. We may feel bored with the day to day sitting, or bored with a particular technique. The whole affair may at times seem fruitless. Here, we can invite the idea of “embracing boredom” by simply noticing it and taking a big step back, observing our response to the boredom. Here, we can cultivate an inquisitiveness as to what lies behind the boredom or behind the veil of our relentless waves of thoughts.

Restlessness can appear as thoughts of what we might rather be doing in that moment. Or we might feel such a resistance that it can cause us to end our practice and head off for our morning cup of coffee or tea. No matter what the obstacles to remaining present and earnest in our practice, it takes effort and time. To quote the Dalai Lama, “practice as if you are going to practice for an eon.” This great effort is referred to in yoga śastra as abhyāsa, or persistent practice. And practice doesn’t stop when we end our sitting practice, but is continued, to the best of our ability, in everything we do, throughout the day. At the most profound level, our sādhana threads itself into the three states of waking, dreaming, and deep sleep, until one abides in one’s true nature. This is known as turīya (pure existence being or eternal awareness).

The act of sitting in yogic meditation is not intended to escape or hide out from the world around us or from ourselves. Rather, it can support us to become more aware of the totality of life, and in a deeper sense, to the abiding awareness of our truest and deepest nature as the Self. It is a concentrated form of spiritual nourishment, which allows this thread of being-ness to weave its way into every breath and experience in life. When we sit in the silence of our practice, it isn’t antithetical to life’s experience, but a method of living more fully in each moment. Here, the most simple acts are infused with the fragrance of being, of pure abiding awareness.

The process of meditation isn’t to gain something afresh that we don’t already have within us, but rather a process of remembering. Here, Babaji would say, “if you have a dollar in your pocket, but you don’t know it’s there, do you have the dollar?” The answer is certainly yes, you do, but in order to be aware that you have that dollar, you have to reach your hand in and find it for yourself. At a certain point, many of us become curious about what is in our pockets, what lies below the surface of our busy lives. This calling to turn inward can take on many forms, but the similarity is a deeper inquiry into the nature and essence of one’s being. There are uncountable paths, practices, and techniques, but the aim of all is to bring one to a singularity of focus, which eventually culminates in a subjective awareness that dissolves the individual self into the one Self, or the soul into God.